War was announced on 3 September 1939. But the ��ѿ��ý had been secretly preparing for years, so that broadcasting might carry-on whatever happened. As these newly-released interviews and documents show, the ��ѿ��ý’s main aim was to protect itself, and the country at large, from the massive and immediate air attack everyone expected.

At quarter past 11, on the morning of Sunday 3 September, Broadcasting House in London faded-out the sound of Bow Bells being played from studio ‘BA’ and switched to 10 Downing Street. The Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was to speak to the nation.

A ��ѿ��ý engineer and announcer had arrived earlier. Everything was now ready, and the engineer signalled to the announcer that all microphones were live.

It was time for him to introduce the Prime Minister by reading the two short sentences typed on a piece of paper in front of him, what the ��ѿ��ý had labelled ‘Announcement B’:

A few minutes later, and after a brief reprise of Bow Bells, the ��ѿ��ý announced that places of public entertainment such as cinemas and theatres would be closed, schools shut, sports events banned, and that in case of bombing or gas-attacks everyone should take shelter as soon as they heard an air-raid siren.

For millions of Britons, and for millions more tuned-in around the world, it would be this broadcast that would be remembered as marking the start of the Second World War.

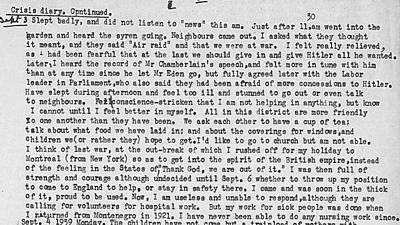

The personal diaries collected by offer vivid evidence of an expectant audience: the woman who ran a fish-and-chip shop in Birmingham, listening at home since 10 o’clock, when the ��ѿ��ý had announced the time-limit for a German response was going to be 11, and thinking Chamberlain’s speech, when at last it came, ‘very restrained’; the seventeen-year-old schoolgirl in Essex, who, along with thousands of others in the South-East of England, heard the air-raid siren sounding in false alarm soon after the transmission from Downing Street had ended and dashed with the rest of her family, gas-masks on, to sit nervously on the staircase – ‘we have no shelter’, she explained.

But many others had not tuned-in. This was not quite a nation gathered around the wireless set as one. Our diarist in Birmingham, for instance, had been looking out of the window as she listened to the Prime Minister and noticed ‘a good many people in the street acting as usual’ – having got up late, perhaps, or having decided to go to church instead.

Among the many thousands who only heard the news second-hand, was Adelaide Poole, a recently-retired nurse living in Steyning, Sussex. Despite this, the day’s events instantly prompted in her a swirl of emotions and memories:

For Adelaide Poole, war had been a foregone conclusion. In the week before she had gone to Brighton to ‘relieve the tension’ by avoiding the wireless altogether. ‘I must guard my own nerves and health’, she wrote in her diary. ‘What is to come, will come, and I as well as others will bear it as best we can.’

In Birmingham, Sunday’s announcement was seen ‘just as confirmation’: ‘people have regarded us as at war since Friday morning’.

It had been on Friday 1 September that the ��ѿ��ý brought news that Hitler’s forces had invaded Poland.

This, two days before Chamberlain took to the airwaves, was the moment when millions started listening obsessively to the ��ѿ��ý for the latest updates.

In Essex, our seventeen-year-old diarist had spent Friday helping her teachers. At 11 o’clock, she went to the staff room, where a wireless set had been installed the day before.

There, she wrote, 'we listened to the announcement that “serious developments in the international situation” had occurred... At break, everyone was asking everyone else, "Have you heard the news?" or "Has there been any more news?"'

The ��ѿ��ý also announced some dramatic – and rather mysterious - news of its own on Friday: in a matter of hours there would be changes to the wavelengths on which everyone listened:

Though the ��ѿ��ý’s announcement about wavelength changes did not immediately say so, the effect was to shut-down the two services which people had been listening to for years, the National Programme and the Regional Programme, and replace them with just one: what would henceforth be called the '��ѿ��ý Service'.

No explanations were given. Nor could they be, since the creation of the ��ѿ��ý Service was a matter of national security.

For several years, it had been assumed by military planners that the outbreak of war would provoke an immediate – and potentially devastating – air attack.

It was also feared that the signals from the ��ѿ��ý’s powerful transmitters would help guide enemy aircraft to their targets. One obvious solution would be to shut-down transmissions altogether in the event of hostilities, though that would also mean no broadcasting at all for the duration of the war.

The ��ѿ��ý’s engineers set about looking for an alternative plan, something that might allow them to continue broadcasting without helping the enemy.

In this newly-released oral history interview, we hear from one of those working secretly on the problem: Harold Bishop.

The ��ѿ��ý’s need to ‘synchronize’ their transmitters lay behind the creation of the single ‘��ѿ��ý Service’. But it was just one change among many at the ��ѿ��ý: the Corporation had been busy with all sorts of other preparations – especially since the Munich Crisis of 1938, when war had suddenly seemed likely.

The document below was pulled-together by senior ��ѿ��ý planners throughout the summer of 1939, ready to be issued to staff in an emergency. It represents a ‘War Book’ of new rules and procedures that had been worked-out over years and put in place from 1 September.

Its language is often alarming. It warns, for example, that ‘an air attack literally out of the blue is very possible’. But its main purpose is to explain calmly the new and highly unusual conditions under which the ��ѿ��ý now operated. It details the protections needed for broadcasters, how staff would be lost to military service, how rationing and shift-work would be introduced, that television would cease.

It also reveals how facilities and whole programme-departments were to be relocated away from London. Its thoroughness is a testimony to ��ѿ��ý planning. But it also reveals the extent to which the ��ѿ��ý feared it would be working under siege conditions from the very moment war was declared:

Listeners, of course, knew nothing about these plans. In particular, they were kept in the dark about a sudden mass exodus of staff from the ��ѿ��ý’s traditional headquarters, which began on 1 September.

Since the Corporation really was determined to stay on air whatever happened, it couldn’t risk keeping resources concentrated in the capital, or indeed in any one big city.

Announcers would continue to declare on air that ‘This is London’. But in reality, many of the ��ѿ��ý’s most famous wartime programmes would be broadcast from makeshift studios lashed-up in converted theatres and church halls in places such as Bristol, Weston-Super-Mare, Bangor, and Bedford.

In this newly-released interview, one of the ��ѿ��ý’s most famous wartime announcers, describes how he watched these plans for ‘dispersal’ develop – and how the removal of whole departments from London began to change the culture of the ��ѿ��ý in profound ways:

John Snagge’s account, like many versions of the ��ѿ��ý’s wartime story, focuses on the experience of senior staff and famous personalities – like the Head of Drama, Val Gielgud, or the Director of Music, Adrian Boult. But the ��ѿ��ý Oral History Collection occasionally offers us the testimony of less well-known figures, with very different tales to tell.

In the following interview, we hear from John Daligan, a young lift attendant in Broadcasting House.

Snagge and Gielgud and Boult were among those designated ‘Category A’, their services to the ��ѿ��ý judged as vital to its wartime role. Those in Category B were to go home and await a summons. Daligan was in Category C. His services were deemed as no longer required and he was ‘free’ to join the armed forces or one of the main civilian defence organisations.

For him, the beginning of September therefore represented a significant – and memorable - moment in life:

In his description of the ��ѿ��ý’s evacuation, Daligan mentions in particular Wood Norton Hall, near Evesham. This was a country house the ��ѿ��ý had secretly obtained earlier in 1939, not just for several hundred of its programme-makers but as a ‘substitute headquarters’ for the entire broadcasting operation, should London ever have to be abandoned altogether.

The ��ѿ��ý’s search for a secluded country base, where it could carry on its work and be in close contact with Government, is revealed in the document below, a 1938 memo the Corporation submitted to the ‘Committee of Imperial Defence’ - which also shows how worried the ��ѿ��ý was about the threat to its own transmitters:

In time, nearly a thousand of the ��ѿ��ý’s staff, more than a quarter of its entire workforce, would be based at Wood Norton, or ‘Hogsnorton’, as it was soon affectionately called by its new inhabitants.

Among those who arrived that first weekend of September, and whose memories of the time are preserved in the ��ѿ��ý Oral History Collection, was Clare Lawson Dick, who would become a Controller of Radio 4 in the 1970s, but who back then worked in the 'Registry':

While Clare Lawson Dick enjoyed the panelled library inside the main house at Wood Norton, a large number of other workers were based in outbuildings scattered around the grounds.

Many worked for the ��ѿ��ý’s new ‘Monitoring’ unit, which had recently been established there to eavesdrop on the output of foreign radio stations, so that the ��ѿ��ý’s newsroom, and Government departments, had access to the most up-to-date ‘open source’ intelligence.

This required sensitive aerials to be erected on a nearby hill and an elaborate set of dedicated cables and teleprinters to allow Wood Norton to communicate with London.

The ��ѿ��ý’s Monitoring service expanded rapidly, which meant the arrival at Wood Norton of more and more foreign-language speakers, many of them refugees from Nazi Germany and occupied Europe.

Along with their new colleagues in Drama, they all needed to be billeted among the bewildered townspeople of nearby Evesham.

One of those charged with making the administrative arrangements was Stuart Williams:

As it turned out, not everyone did need to be at Wood Norton. The evacuation of London, though long envisaged, didn’t run entirely smoothly. And it was quickly realised that some staff who had been bussed there might need to return.

Among these was Mary Lewis, a young clerk in ‘Duplicating’, the section responsible for typing-up and copying programme scripts and important documents:

Mary Lewis’s hasty trip to Wood Norton, and her equally hasty return to London, spoke volumes about the state of the ��ѿ��ý as war broke out.

For years, it had been secretly planning for this very moment. In particular, it had set out an elaborate scheme of dispersal and protection designed to withstand an imminent and overwhelming attack from the air.

Yet war rarely unfolds in predictable ways. And in September 1939, the first experience of most British listeners would turn out to be not so much devastation and terror as simple boredom.

Further Reading

- Asa Briggs, The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom, Volume III: The War of Words 1939-1945 (1995)

- Juliet Gardiner, Wartime: Britain 1939-1945 (2004)

- Dorothy Sheridan (ed.), Wartime Women: A Mass Observation Anthology 1937-45 (2000).