Busoni: music’s forgotten visionary

At the turn of the 20th Century, the name of Ferruccio Busoni was on the lips of music-lovers across Europe. But 150 years after the composer’s birth, contemporary concert goers barely know who he is. With Tom Service.

Last on

More episodes

Previous

20th Century pioneer

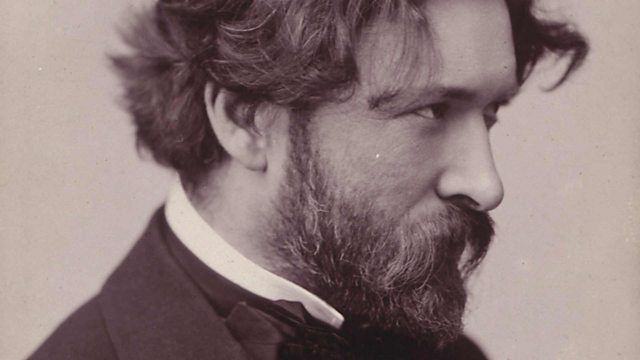

At the turn of the 20th Century, the name of Ferruccio Busoni was on the lips of music-lovers across Europe. Concert-goers would have known his performances - either at the piano or from the conductor’s podium. Pianists flocked to his masterclasses, and other composers set their compass for Berlin, the city Busoni made his home. But 150 years after Busoni’s birth, contemporary concert goers barely know who he is.

To uncover the art and philosophy of this indispensable figure of world culture in the 1900s, Tom Service visits the German capital with conductor and musicologist Antony Beaumont, who wrote a biography of Busoni, and made a completion of his magnum opus, the opera Doktor Faust.

Having made the role of Faust his own, US baritone Thomas Hampson unpacks the sound world of Busoni’s opera, while Beaumont describes the melting pot neighbourhoods the composer was drawn to, and the way in which he collected the best of what he found in his favourite haunts.

Bach devotee

Busoni’s father introduced him to the music of J S Bach. Erinn Knyt of University of Massachusettes Amherst outlines how Busoni’s boyhood compositions featured fugues and inventions imitating the Baroque master, and the lasting imprint they left on his compositional vocabulary.

Working to an ideal of no composition ever being quite finished, Busoni would happily alter notes in other composers’ works – something he was criticised for in his lifetime, along with piano playing that some rejected as too cold or objective. But Knyt argues that Busoni’s astounding technique and cerebral approach foreshadowed the piano style of the later 20th century.Free music

Dr Thomas Ertelt of the State Institute of Music Research in Berlin, and Dr Michael Lailach of the Berlin State Museum’s Arts Library introduce images of Busoni with some of the pupils who looked to him for fresh inspiration after the horrors of WW1.

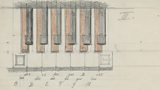

And they offer an insight into the composer’s concept of a new ‘free’ music – which included a third-tone scale to be played on a specially commissioned reed organ.

Busoni never composed for the instrument, but Dr Ertelt has reproduced the sound of the third-tone scale, which provided inspiration in the world of electronic music.Undiscovered masterpiece

Pianist Peter Donohoe explains why some conductors are so reluctant to take on Busoni’s monumental concerto – a piece he hails as “one of the world’s great undiscovered masterpieces” - and the joy of playing ‘sublime’ passages he describes as among the greatest in the concerto repertoire.

And Svetlana Belsky of the University of Chicago discusses the love and reverence with which Busoni approached his many piano transcriptions of J S Bach’s compositions.

Credits

| Role | Contributor |

|---|---|

| Presenter | Tom Service |

| Interviewed Guest | Thomas Ertelt |

| Interviewed Guest | Michael Lailach |

| Interviewed Guest | Thomas Hampson |

| Interviewed Guest | Svetlana Belsky |

| Interviewed Guest | Erinn Knyt |

| Main Busoni image, Oppenheimer Busoni portrait and third-tone keyboard sketch | Staatliche Museen zu Berlin |

| X-ray image of Busoni's hands | Schiff Institut für Radiographie und Radiotherapie |

Broadcasts

- Sat 3 Dec 2016 12:15��ѿ��ý Radio 3

- Mon 5 Dec 2016 22:00��ѿ��ý Radio 3

Knock on wood – six stunning wooden concert halls around the world

Steel and concrete can't beat good old wood to produce the best sounds for music.

The evolution of video game music

Tom Service traces the rise of an exciting new genre, from bleeps to responsive scores.

Why music can literally make us lose track of time

Try our psychoacoustic experiment to see how tempo can affect your timekeeping abilities.

Podcast

-

![]()

Music Matters

The stories that matter, the people that matter, the music that matters