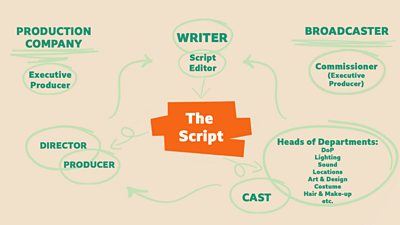

This is the third part in a series of blog posts for screenwriters who are keen to understand more about the steps involved in making their project into a reality. It covers the production stage of a script reaching the television screen, which follows from a greenlight from the broadcaster's Commissioning team. Once the greenlight has been given, the production enters the preparation stage, followed by the actual shoot.

A production will obviously vary enormously depending on the project involved. In order to provide some real-life context we've spoken to some members of the team behind the 2025 BAFTA winner for Best Drama Series, Blue Lights, about their experience in bringing that drama to the screen.

As explained in Part One of this series of blog posts, no project will ever be commissioned by ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ Drama without a production company first being involved ( in the case of Blue Lights). The approach to ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ Drama Commissioning is always via this production company who may have been working on developing the show with the writer for several years prior to pitching it.

Part Two set out how achieving a greenlight from Commissioning is an incredibly competitive and sometimes frustrating process, as lots of different variables come into play, many of which can be outside the control of the writer.

However, if you are lucky enough to be the writer of a drama which does eventually gain that elusive greenlight (in other words it's going to be made), then this is when things will really crank up, with all hands on deck to produce the best possible version of your script for the screen, within time and budget constraints.

Find out what production was like on Blue Lights and how each area works with the script, from one of the show's Writers, its Script Editor, one of its Directors and the Head of Costume by reading interviews with them below.

The Writer

Blue Lights is written by together with his writing partner .

Hear from Declan about his experience during the production of Blue Lights.

(Click on each job title below to read the interviews).

When Blue Lights was commissioned what was this from? A treatment, pilot script, series outline?

First of all, the ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ put the show into development. That meant they greenlit a script and a writers’ room. After the room, we wrote a series bible and then rewrote the pilot significantly. Not long afterwards the ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ greenlit the show – as these things go it all happened relatively quickly.

When you got the commission greenlight how did the process escalate?

Things changed instantly. Blue Lights went from being one of several projects we were developing, to our central focus. Suddenly the practicalities kicked in. For the producers those must have been wide ranging and eclectic but for us it came down to one main question: When could we deliver the scripts?

Who works with you at this point? Eg Script Editor/Producer/Executive Producer/other writers (eg in a room)?

On that first season we had various storyliners in the room, and to help us write it. came on board. At that time she was a trainee script editor – but after 18 episodes of television in three years she’s now the script editing final boss.

The core creative team was me, Adam, and . And in season one, the ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ Exec (Commissioning) was , who did a great job. By this point, I already knew that screenwriting was an intensely collaborative art form, but those months were an even greater education in that. To be a good TV writer you take notes, assess them, use them, and always try to retain that central vision you have for the show. I actually like working that way. I like being around people and working as part of a team.

How do you know when you’ve reached a final shooting script for an episode?

I don’t know but if anyone ever finds out please tell me! You’ll be writing revisions all the way through shooting. Some changes are for logistical reasons – maybe a location is no longer available, maybe an action sequence just doesn’t square with the budget and you have to think again. Some are for creative reasons, when actors or directors come up with an idea and you decide to go with it. Even after you finish shooting, you are still writing in the edit, changing focus, adding something or dropping something. I genuinely feel that I’m still writing until the day we lock the episode.

How many drafts do you (roughly) go through?

Once you have a production draft – which itself takes many drafts – you then move in to colour codes of revisions of scripts. You might start with pink… then blue… then yellow… it goes on and on.

I was told by a very experienced Head of Department recently that in her thirty years in the business, she had never seen somebody reach a particular colour code in the production revision scripts. BUT SOMEHOW, I HAD ACHIEVED THE DIZZY HEIGHTS OF “DOUBLE WHITE”. I accepted this as a badge of honour. We really do a LOT of changing as the show takes shape.

I think this is because Adam and I don’t just write on the show; we also executive produce it and direct some episodes, so we see the writing as one element of a big creative canvas that is constantly evolving.

As an example; Blue Lights is fundamentally a character drama. Each main character should have a definitive arc in any season. As we bring those arcs in to land in episodes five and six, sometimes we have insights about how we have set them up in episodes one and two. So, we go back into those earlier scripts and change them accordingly.

This means on paper, Sarah might have dozens of drafts of each episode that we have retrospectively changed for all sorts of creative reasons, but the good news is she has not yet resigned.

What do you learn from a read-through?

Mostly we learn about all the lovely foreign holidays the actors have taken whilst we have been writing the show.

In reality, we all do love read throughs. In many ways that’s where you find out if an episode is working. Does it feel slow anywhere? Do people laugh at the bits you think are funny? Are they laughing at bits that are not supposed to be funny? If you hope you have struck an emotional chord on paper, can you feel it in the room?

Directly after a read through all of the executives from the ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ and the production company () get together in a room and we talk about all of that, and some of the most valuable notes we get come from those meetings.

Then… guess what?… we go and do some more rewrites.

As Executive Producers what extra decision making and input do you have that other writers might not?

We’re across all of the creative decisions, so we get a say in casting, who the director is, who the Heads of Department will be. We watch the rushes every night and give notes where appropriate. When it comes to viewings we attend the edit and give notes on the cuts.

TV scripts are like an architectural blueprint; it’s good to be able to have a say in how the house is going to be built. Because all people ever get to see is the house, not the plans!

Can you give an example of some of the practicalities that cause changes to the script during the shoot? For example, any obstacles or issues that cropped up that required changes?

There are so many different things that might require scenes to be changed. One very simple one is that the crew might have a big shoot the next day, trying to get through several pages, and the producer might ask if there’s any way for a scene to be shorter so they can make the day. It’s incredible how much you can shorten a scene and still have it deliver everything you need it to.

Maybe a location suddenly isn’t available and you have to write the scene to take place somewhere else.

Maybe the director or one of the actors has some insights into the scene, and wonders if they can do it a different way that feels better to them. Then you might sit down with them and see if you can reach agreement on how to do it.

The list of reasons why you might want to do a late rewrite is endless.

How flexible do you need to be to change?

Screenwriting is, at heart, problem-solving. Using every ounce of your creativity to overcome obstacles big and small whilst retaining the artistic viability of the writing. If you like doing that, you’ll be very happy as a screenwriter.

The other thing you need to realise is; other people have great ideas.

If you can sit in notes meetings and genuinely listen with an open mind – an open heart maybe – you will hear those great ideas all the time. Maybe they come from ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ execs, or producers, or the director, or an actor.

I have heard ideas from actors on Blue Lights that fundamentally changed my conception of their character, and even made me think differently about the show.

So, I would say that your first duty is to have something meaningful to say in your work. Your second duty is to be open to allowing other people to help you say it.

How do you cope with the time pressures of production, making amends through the shoot etc?

It’s frenetic and all-consuming. In every season of Blue Lights there has been a moment when I have sat quietly by myself and thought – “I can’t do this” as I idly scroll through available flights to Brazil that are leaving immediately.

Then, after some meditation and cursing (in no particular order) I drag myself back into it.

This makes it sound terrible; in reality, myself and Adam tend to thrive under pressure. We like to be busy. In many ways it reminds us of journalism, when you are really up against it on a huge story and trying to get it done on a deadline.

Who is your point of contact throughout the process?

Sarah Hewitt for scripts. Stephen Wright and Louise Gallagher for general creative. Nick Lambon and Heather Larmour at the ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ for notes and insights. The producer as the bridge between the set and the office.

What are some of the key things you learnt from Series 1 and 2 that you’ve been able to apply going forward?

People might come to TV shows for the premise, and be entertained by the plotting, but they stay for the characters. It really is the most important thing for us. You have to build the characters and you have to love them and care about them, even the baddies. Especially the baddies.

In a wider sense, enjoy the process. Sometimes we can be overwhelmed by the enormity of deadlines, or the pressure of production, or the day to day difficulties of working in a huge team.

But it’s important to have as much fun as possible, because writing television drama really is the best job in the world.

The Script Editor

is a Script Editor at Two Cities TV, the company behind Blue Lights. She has worked on the show since its first series back in August 2021. Sarah also works in Development for Two Cities alongside her work on Blue Lights.

Hear from Sarah below about her role and how she works with the script during preparation and the shoot.

How does being a Script Editor in production differ from in development?

In development, we throw every idea at the wall - or in our case a few large whiteboards in the Writers’ Room. It’s best at that stage to not let practicalities of shooting limit the creative flow too much, and to just enjoy the possibility of every idea, big or small. In production, we need to consider how the ideas work with filming, involving input from every department.

In prep, budgets need to be considered, but there are many other aspects that need to feed in, for example:

- Weather - a scene set on a warm summer’s day will prove tricky in January, and closer to the time, a sudden shift in weather could cause us to partially rewrite a scene for an indoor location. When Storm Éowyn hit during the filming of Series 3 of Blue Lights, our schedule was affected for health and safety reasons, and every department had to work together on short notice to make sure we could pick up any scenes that would be missed, and also consider if there were any that we could cut or condense.

- Cast availability - while we know in advance when cast are available, circumstances beyond our control, like cancelled flights for example, might occasionally mean a cast member isn’t available at short notice. The crew will try where possible to reschedule their scenes for a different day, but sometimes this isn’t possible, and that’s when it can fall to the script department to ease the pressure. We first consider if a scene can be cut - will the story still make sense? Will the character’s arc still seem complete? If not, we might look at scenes involving the character that are scheduled to shoot on a different day, and work with the writer to edit those to include any vital story information or character development that would be lost otherwise.

- Locations - the way a scene was originally written might not suit the chosen location. Perhaps a house is laid out differently to how we had imagined, or a road closure isn’t possible for a car chase.

- Advice from other Departments - In the lead up to filming, we also accept input from a range of other departments - police advisors might tell us something isn’t procedurally accurate, and while we do take some artistic license if it’s what’s best for the story and characters, we try to be as realistic as possible. Art, Costume, and Hair & Make-up also draw our attention to things in the script that they know will make things difficult on the day. If a character spills a drink on themselves for example, that cast member might have to change and be dried for each take, and we might consider an alternative.

We liaise with the Assistant Directors often when they are scheduling the scenes. It might be that losing half a page from a scene can take a nearly impossible day to something that can be shot on time. As Script Editor, I might mark up lines that we can cut or condense alongside my trainee, then we go to the writers with our suggestions so that they can be edited in the script.

While in development, we are in our writing bubble with a small team, production becomes a time to consider the impact on every department possible, and what we can do in the writing to help the filming run smoothly while still retaining the integrity of the scripts.

What does your role involve?

As a Script Editor, you are ultimately the protector of the scripts and the story. We act as conduits between the writers themselves, and the production team and all other departments. Rather than go to the writer with a problem that has been flagged, we try to come up with creative solutions that still serve the story and characters, and then workshop them to the writers who will then put them into the scripts.

As a Script Editor, you are there to both assist the writers creatively, and support the production team to ensure everything is practically possible for them. While it can be hard to cut a scene, character or sequence for practical purposes, it also presents an opportunity to work collaboratively with the writers to come up with a solution that works just as well. Sometimes we stumble across an idea in that process that actually is better than what we had originally - that’s always a treat.

In production, I’m involved in various meetings and events that I wouldn’t normally see in development. For example, I attend all of the recces, when we visit our filming locations, sometimes involving a few long drives to beautiful places I would never normally have access to outside of the job. On the recces, I consider how the layouts of the locations might affect how they are written in the script. The Director might see something on location that sparks an idea for a shot that hadn’t originally been planned. They would then speak with me, so I can feed the information back to the writers to edit the script and make the most of the location.

How do you manage different drafts? Is there a naming convention?

While in development we name and date drafts, Draft 1, Draft 2.

We have to stay strictly on top of things in production to ensure every member of the cast and crew are working from the correct draft. When we start production, we move to a Production Draft. This is a draft that is quite close to what we will film, but as the various departments start working, it goes through a series of edits based on practicalities of filming. In preparation for the read-through (when the cast and crew sit down for a reading of the scripts) we prepare a Read-through Draft. This draft incorporates practical notes, alongside any other creative ideas that have come to light. Sometimes someone has a lightbulb moment at short notice that’s too brilliant not to include, or a note that isn’t obvious until you hear a script read out loud by the cast. At that stage we might realise that a few lines of dialogue need to be trimmed for pacing, or that a sentence doesn’t sound as natural as it looked on paper.

We make these minor tweaks and issue what is called our Shooting Script. This is the script that is used for filming. Of course, changes can and will still be needed. During shooting, we colour code our revisions, starting with pink, to make it clear which version of the script we are working with.

Are you there on set during shooting?

On Blue Lights, I’m lucky that many of the main sets are near the production office - our police station is in the same building. Similarly to a read-through, hearing and seeing the script come to life can spark ideas for characters and later episodes, so it’s important to visit the set. If I have an urgent script note to address but need some input from the producer or director, it’s better to go to set and talk in person when they have a moment between takes, rather than send an email. It’s also a nice opportunity to get out from behind the desk and get to know the cast and crew.

The Director

is a director who has worked across all three series of Blue Lights.

Find out below how Jack works with the script and its writers.

What do you look for when reading through the script?

The first read is purely for enjoyment. I try not to think about how I’ll shoot it or what the logistics might be, I just live in the world, sit with the characters, and enjoy meeting any new ones. That’s always the best read. It gives you a feel for the pace and rhythm of the piece, and starts to hint at the tone.

At that stage, I might speak with the writer, especially if I’ve got questions about later episodes, story logic, or a character’s arc. It’s useful to know where things are heading as you begin to map out the storytelling.

The second pass is more analytical. Still exciting, but now I’m starting to visualise the world: where it’s set, how it feels, how we might shoot it. Images form in your head. The kind of lighting you want to use, lenses you’re thinking of, what the atmosphere might be in each scene - starting to form ideas of references to other material which helps to convey your ideas to the creative teams.

It’s important to share that vision with the writers and producers, making sure we’re aligned in how we see the world, the tone, and the detail of the characters.

Then comes the recce phase, looking at locations, studio builds, and starting conversations with key heads of department — producer, designer, DoP. What we find on those recces often feeds back into the script.

Sometimes it’s a case of, “We’ve found the rooftop you wanted. It ticks all the boxes and works for crane access, it even fits the safety brief but there’s no view of the city…”

Other times it’s more like, “We’ve found this incredible location with a tunnel entrance. Could that be written into the action?”

The script is the compass for every department. It’s vital that any creative changes, whether practical or story-driven, are reflected in the script as it evolves. If that slips, it can cause problems further down the line, especially on the shoot. Script editors are an essential part of this process too.

Once the 1st AD begins to build the schedule, patterns start to emerge, maybe a location is overloaded or underused. That’s when I’ll go back to the producers, script editors or writers to see if scenes can shift around, or if we can expand something in a particular space to help balance the schedule.

As the locations get signed off and the shoot takes shape, it becomes a bit of a puzzle, trying to make every day count while still honouring the story and the vision we all set out to achieve.

What helps you to do your job most effectively?

Collaboration, from the top down. Being able to have open, creative conversations with people who all want the best for the show is what makes the job work.

It starts in pre-prep with execs, producers, and writers, shaping the script and figuring out how to get the most out of the budget, to ensure as much money ends up on screen as possible.

Then your HODs come on board: Designer, DoP, locations, costume, makeup. You share your vision for locations, scenes, sets, and characters, and then build on those ideas together. That’s how you start to create a stronger, more unified visual world, one that’s richer because of everyone’s input.

That spirit of collaboration continues into the shoot with sound mixers, art department, action vehicles, stunts. You’ll be asked a thousand questions a day, and the clearer your prep was, the easier it is to respond confidently and keep things moving.

Actors play a big part in that too. They bring fresh ideas, instinctive choices, and often unlock something unexpected in a character. I always try to feed that back to the writer, not to change the script, but to deepen the character or emotional truth. That dialogue between performance and writing is really important. Sometimes it may happen on the day but I'll always try to avoid this and meet with cast and discuss the script in my prep stages - stumbling across a problem on set can be time consuming and often on set you don't have access to the writer to verify any concerns.

Underpinning all of it is preparation and communication. You need to understand the script inside out, know where the emotional beats are, what drives the story, what the tone is, but you also need to stay open. Open to the team around you, to new solutions, and to the idea that things might evolve. That’s what keeps the work alive.

And lastly, staying calm helps. The director sets the tone on set. If you can stay steady under pressure, keep a clear head, and problem-solve without fuss, it allows everyone else to do their job with confidence.

What are some of the common problems that you come across?

Time and budget. You never have enough of either. The schedule is always tighter than you’d like, the ambition nearly always exceeds the spend. So you learn to be ruthless with your prep. You need to know what matters most in every scene. What can’t you compromise on? What’s the emotional core? What can't you live without? Once you’ve got that, you can work around the rest.

Locations are another regular one. Whether they match the script expectations or come with restrictions; logistics, tone, noise — you’re constantly rethinking things with the DoP, designer, locations team, or going back to the writer to see if a small shift keeps the scene alive in a new space or the action can be reworked to help fit said space.

Tonal consistency can be tricky too, especially on a multi-block show. You might be directing scenes that sit right next to someone else’s work, and if the tone’s off by even five percent, it jars. So communication is key, regular chats with fellow directors, producers, and the writers to make sure we’re all aiming for the same thing.

Then there’s the weather. Always. You can plan a beautiful crane shot at sunrise, and wake up to horizontal rain and low cloud. So you get good at letting go of what you thought the scene would be, and finding a version that still works — maybe even something better, sometimes.

Most problems come down to flexibility, knowing when to hold your ground and when to adapt. And that’s where having a strong team around you makes all the difference.

How do you feed these back and potentially ask for changes?

It depends on what the issue is, and when it crops up.

If it’s in prep and the issue is script-based, like a scene not quite working emotionally or feeling logistically impossible in a certain location I’ll speak to the producer and script editor, or the writer directly if they’re available. That conversation’s always framed around story and character first. So not, “We can’t do this,” but, “Is there another way to get to the same moment, given what we know now?”

Writers and producers are usually very open to that, they want the scene to land just as much as you do. As long as you’re clear, respectful, and have thought through the alternatives, they’ll hear you out.

Time and money tend to come from the same pot. The more time you need, the more money it costs. So if an action sequence requires three days to film but the schedule only allows for two, you either need more money to give you more time, or you need to look at the script and trim some of the action. It’s always better to do that on the page than in the edit. Having a tight script in that aspect means the writer has more control over what actually stays in the show.

If it’s something technical, maybe a location isn’t safe, or a shot won’t work with the gear available, then that goes through the relevant HODs first: DoP, designer, 1st AD. Together we might tweak the plan, then feed that up to producers and across to editorial. It’s about finding practical solutions, not just flagging problems.

It all comes back to communication again, and timing. If you raise issues early, there’s usually space to work through them without it becoming a big deal. But if you stay quiet and spring it on the day, you create pressure for everyone.

And sometimes, changes come the other way too. From editorial, production, or even the channel. Maybe a scene’s too expensive, or a storyline needs shifting across blocks. In those cases, it’s about staying flexible and keeping the creative integrity intact as you adjust.

Ultimately, it’s about trust. If everyone feels like we’re all trying to make the same show, not protect egos or fight for territory then those conversations stay constructive.

How do you deal with changes to the script that can be due to issues that are out of your control, for example at the last moment?

They can be frustrating, even heartbreaking, especially if it’s a moment you’ve all been building towards. But if the creative team has been clear from the start about what really matters, the core story beats, the emotional spine, then you’ve got something to protect. And that makes decision-making a lot easier when things get tight.

The job then becomes about prioritising: What can change? What can’t? What’s the version of this scene that still lands the same feeling, even if the details shift?

It’s also about adaptability. The classic example is weather. It’s forecast sunny, and you’ve planned to shoot your wedding sequence… and then the heavens open.

What’s the backup plan? Have we found a second option on the recce? Can the scene move inside, or could the rain actually add something to the moment?

You always need a Plan B. That doesn’t mean playing it safe, it means being prepared, and knowing how to pivot without losing what matters most.

Head of Department: Costume

As a script shifts into production heads of all the different departments involved will come on board, including design, DoP (director of photography who heads up cameras and lighting), locations, costume, makeup, sound and more.

has been the costume designer on many television productions, including Blue Lights since its inception in season 1 and then on season 2 and 3.

Find out from Maggie how she works with the script during the production of the show as the head of the costume department.

How do you work with the script? What do you look for when reading it through?

When I get the script, I read it through and then re-read it to set the context firmly in my mind. I am looking at first and foremost the story and getting an understanding for the characters within that story.

Bringing these characters to life is the main objective for a costume designer so it’s important to have a good understanding of their background, their mindset and their role in the story. For me, that’s the beginning of the creative process before any mood boards etc.

In season 1 every character in Blue Lights was a new born entity and that was exciting helping bringing them to life. So, what is written about them, their back story was essential for getting an understanding for their character. For instance Grace’s character was a social worker before becoming a police officer, she was a single mother, had empathy for the people she came across. So, basically I’m forming in my head a good knowledge of this person from what I am reading about them before the next level of speaking to the director about the mood and tone of the piece that will affect palette and thoughts about each character.

Also, in terms of uniform, what uniforms are we looking at for cast and supporting cast.

What helps you to do your job most effectively?

A good working relationship and common understanding with producers, directors and of course the actors of how we want the characters to look.

I think it is very important to work closely with actors regarding their character and how it is reflected in what they wear, their colour palette and what they feel comfortable wearing.

Also, within the 3 seasons of Blue Lights all our principal cast have evolved in their character and storyline, which is reflected in their clothes choice. For example, Tina, when we find out at the end of Series 1 that she was the real power behind the Mcintyre crime family. So, her choice of clothes change from a brash housewife in her leggings, loud colour palette and leopardskin boots to a more upmarket monied look. (Although she still keeps her own Tina-style with her gold hoop earrings and still a touch of animal print but now in cashmere!)

Having a good working relationship with make-up and hair and production design is also important - getting to know their thoughts on how a character looks from their perspective and their choice of background.

All this feeds into the overall look. Visuals and mood boards are essential to ensure we are all on same page.

Also having a good support team within the costume department is essential to enable me to focus on the creative process. Doing plenty of background research particularly in the case of Blue Lights with the PSNI (Police Service of Northern Ireland) uniform etiquette and having our police advisor is essential.

Having locked scripts or an outline of the plot and number of characters so we know what to expect and how to budget for that.

What are some of the common problems that you come across?

Late scripts, late casting, late schedule are constants in this business and we deal with them all as best we can.

From a script point of view, what might be a potential worry is if there is a big visual effects /stunt storyline or scenes with large numbers of uniformed extras in, for example, large scale riot scenes which have featured prominently in Blue Lights Series 2. How we deal with that, and where it comes in the schedule is important as we need time to source the uniforms and fit our cast and supporting artists.

Or if a character is getting injured in action, we need to know how many repeats of clothing are needed and if stunts are involved.

How do you feed these back and potentially ask for changes?

On every production we have weekly meetings in prep with all departments present, so that is the time to ask questions pertaining to our issues re what is scripted and how production can help us.

It is also useful to have all the other departments there as we all feed off each other. So, for instance the production designer can show me colour palettes of background which is essential to know when I’m working on my own colour palette for characters.

I think working as a team for the good of the production and knowledge of what is coming ahead for characters is essential.

I can’t think of ever asking for many changes to the script except in practical terms of numbers as to what we can provide in uniform. For example, in Blue Lights Series 2, in the scene where Rab is hit and burned by a petrol bomb, it was scripted that he was set on fire wearing his band uniform. That would have meant a big cost for repeats to be constructed for the actor and the stuntman. It worked better for the storyline and for costume that he was in civvies and that was changed accordingly.

How do you deal with changes to the script that can be due to issues that are out of your control, for example at the last moment?

That often happens in this business. Firstly, keep a cool head! Then just deal with them! In all Blue Lights seasons there have been changes to script, some indeed last moment. It might be a location change due to weather or an actor not being available for whatever reason. Also, the director may want a character in civvies for a scene instead of uniform. So, it’s important to have a good knowledge of the script and be open to any changes needed to be made and deal with them as professionally and creatively as I can.

Also, the stock amassed over the years and hired to Blue Lights which travels with us allows for last minute changes to a certain extent and the embargo from previous seasons eg change of scenes from uniforms to C3 detective look, we carry suits etc. Principal cast all have a wardrobe of civvies as sometimes scenes are re written to take place at the end of the day in civvies not in uniform.

As has been made clear by all the contributors to this blog post, trust and collaboration are absolutely crucial ingredients for a successful television production.

The script is an ever-evolving document, and as its writer you need to be open and flexible to constant changes and revisions which can come from circumstances that are outside of your control. Because of this your script can never be regarded as a finished document. An openness to collaboration and an enjoyment of teamwork are what make a great TV writer, perhaps to a greater extent than any other form of writing.

That openness to change continues into the final stages of bringing your script to screen - the Edit and Broadcast - which will be the subject of the final part of this series of blog posts.

Related Links

-

How To Get Your TV Script Made Part One: From Your Idea to Commissioner

-

How To Get Your TV Script Made Part Two: The TV Drama Commissioning Slate

-

Blue Lights Watch on ÃÛÑ¿´«Ã½ iPlayer

Latest blog posts

More blog postsSearch by Tag:

- Tagged with Blog Blog

- Tagged with 2025 2025

- Tagged with Script to Broadcast Script to Broadcast