Dino guide: Creating Edmontosaurus and pterosaurs

by Jay Balamurugan, series assistant producer

Our heroes live in vibrant prehistoric worlds, teeming with life. In The Journey North, we meet some of the weird and wonderful animals that live alongside them. Emphasis on weird.

a group of flying reptiles that dominated the skies for over 160 million years

In The Journey North, toddler Albie has a close call with an airborne predator – a giant pterosaur. These animals are not dinosaurs but a group of flying reptiles that dominated the skies for over 160 million years. They came in all sorts of shapes and sizes, from tiny hamster-shaped insect eaters to needle-toothed ocean divers and apex predators the size of small airplanes. All of them were unlike anything alive today. Across Walking with Dinosaurs, we meet three different species of azhdarch pterosaurs (the massive, long-necked, predatory ones), all of which are very new to science.

To say these flying reptiles are strange is an understatement. Their heads are almost bigger than their actual bodies, their elongated necks mean they stand as tall as giraffes, they are covered in fur-like feathering, and they have unnervingly human-like back legs. Researching and designing these creatures was a very involved task, and I spoke to a multitude of scientists to figure out just how our giant pterosaurs should look and move.

The brief we put together for these animals was extensive, with pages upon pages of anatomical detail. Even then, the VFX model went back and forth between the VFX team, the production team and scientists, more than any other animal. Each time, the feedback was a resounding “It isn’t quite weird enough.” The neck needed to be made longer, the head bigger, the already tiny eye smaller, and don’t even get me started on how those wings needed to fold and shrink up against the body when the creature was grounded. That specific detail took weeks to get right.

Pterosaurs essentially have precision-engineered wings, with fibres that allow them to fold up in such a way that they almost disappear when they are walking, keeping any loose membrane out of the way. Speaking of walking, pterosaur trackways show that despite being powerful fliers, they were confident and capable on the ground, walking very similarly to giraffes, moving the limbs on one side of their body at a time. While I can’t say anyone on the team would be keen on running into one of these guys in a dark alley, the pterosaurs were some of our favourites, and add a real splash of colour to the world our heroes inhabit.

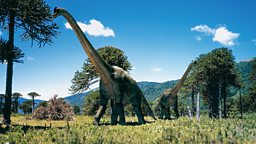

In the late Cretaceous, it wasn’t just the skies that were ruled by oddities. Later in The Journey North, little Albie comes across a herd of giant herbivorous Edmontosaurus. These elephant-sized dinosaurs are part of the hadrosaur group. While you may initially think of them as stock-standard, nondescript, plant-eating dinosaurs, recent fossil discoveries have shown just how remarkable these animals were.

Multiple specimens of Edmontosaurus, including an exceptional one discovered in 1999 nicknamed ‘Dakota’, have been preserved so well that they are informally known as ‘dinosaur mummies.’ These individuals are so intact, that scientists can study their muscles, tendons, skin, beaks, crests, fingernails, and potential patterning. One of these specimens even preserved an entire hoofed hand! This abundance of information revealed that Edmontosaurus was considerably more interesting than anyone thought.

Thanks to these ‘mummies’, we now know Edmontosaurus had an extensive hooked beak covering its duck-billed snout, a large soft crest on its head like that of a rooster, giant oval-shaped bumps on its neck, protruding square scales running in a row down its back, and potentially even a striped patterning across its body. Compared to those pterosaurs, making the design brief for these guys was a dream! I worked closely with palaeontologist and palaeoartist Henry Sharpe, going through each of these elements across the design and VFX stages, ensuring that our final Edmontosaurus model was as true to life as it could possibly be.

After all, not everyone’s favourite dinosaur can be T. rex.

Bringing the supporting cast of creatures to life was a real joy, and by the end of the production, I had developed a real love for these underappreciated gems of the dinosaur world. I hope that audiences will feel the same! After all, not everyone’s favourite dinosaur can be T. rex.