The life of a palaeontologist in Alberta

by Emily Bamforth, curator at the Philip J. Curry, dinosaur Museum, in Wembley, Alberta, Canada

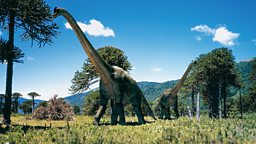

I fell in love with dinosaurs as a very small child - this is a way that a lot of palaeontologists (people who study fossils) get into palaeontology (the science of fossils). I saw my first dinosaur skeleton when I was 4 years old. It was one of the big, long-neck dinosaurs (called Mamenchisaurus), and I just remember being totally fascinated by that animal, and as family lore would have it, that is the moment where I decided I was going to be a palaeontologist. And I've been into dinosaurs ever since.

I saw my first dinosaur skeleton when I was 4 years old.

The first series of Walking With Dinosaurs had a big impact on me. It was around the time when I was getting really into the dinosaurs. Walking With Dinosaurs showed a way that dinosaurs are brought to the screen in a believable way, that wasn't a Hollywood blockbuster. This was really a documentary about dinosaurs. It had a big impact on me as a younger person.

I always knew I wanted to go into palaeontology, from the moment I could choose subjects, I opted for biology and geology – the foundations of palaeontology. Through high school, my bachelor's, master's and into my PhD, I was always studying fossils. And then, I was given the opportunity to come up here to northwest Alberta, to become the curator of The Philip J Currie Dinosaur Museum. Now I specialise in northern dinosaurs, which in the Cretaceous period actually would have been polar dinosaurs. I'm also very interested in fossil plants, which tell us a lot about the world the dinosaurs lived in.

As a palaeontologist here in Alberta, I feel like I basically have two different jobs. I have a winter job, and I have a summer job. Because of our climate, we have a very small window when we can actually get out and do fieldwork, as soon as the snow melts and the ground unfreezes, which is usually in May, and then we go until it literally snows, which is usually October.

we have a very small window when we can actually get out and do fieldwork

A typical day in the field would be in the summer for us. Despite being north, it can actually get quite hot out here, so we try and beat the heat by getting here early. We sometimes have to drive up to two and a half hours to get to a field site. We'll do work at the site. That can be excavation, quarry mapping, we'll study the stratigraphy, we'll collect fossilised plants. And then we can wrap as late as 8 o'clock at night. We are far enough north that we have 14 or 15 hours of daylight in the summer, so we're lucky that way.

And then in the winter, it's almost a different job. My team and I do our fossil preparation in the lab. Of course, we have a big fossil collection in the museum that we're responsible for curating, so a big part of what we do is keeping track of those thousands of fossils that we have in our collections area. We also do a whole lot of work with education and public outreach. Science communication is a critical part of what we do. I love the summer. I love the winter. I love all aspects of being a palaeontologist.

Seeing the return of Walking With Dinosaurs was so exciting. The part for me that was so spectacular was seeing a depiction of the Pachyrhinosaurus mega herd - that huge herd of animals moving across the foothills of the Rockies. It's phenomenal to see the work that we're doing and the science being brought to life. It is a spectacular story.

if you're interested in palaeontology, get out and find some palaeontologists

I would say there is no better time than now to be a dinosaur palaeontologist. There's more public interest than there has ever been in dinosaurs. The great thing that I love about palaeontologists is we do it because we're passionate, because we love dinosaurs, because we're fascinated with the ancient world. So I would say to someone interested in dinosaurs - keep that passion and just pursue it. Take it as far as you can, and if you're interested in palaeontology, get out and find some palaeontologists. The best way to get into it is to meet those people doing it!