Context and clues: Reconstructing prehistoric worlds

by series assistant producer Jay Balamurugan and showrunner Kirsty Wilson

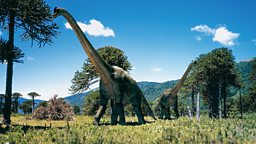

In Walking with Dinosaurs, palaeontologists are captured unearthing the remains of some of the most magnificent creatures to have ever walked the Earth. From leg bones as tall as a person to claws as sharp as daggers, each bone uncovered tells us more about these incredible animals. But no matter how complete a specimen, questions remain.

clues come in all manner of different shapes and sizes

Even with multiple complete skeletons, it is hard to determine what a T. rex ate. Of course, we know it ate meat – those giant, bone-crushing, banana-sized teeth were clearly not for biting through leaves. But did it eat only specific species of dinosaur? Or a wide range? Did it target the weak? Or could it take on healthy prey?

To build up a more complete picture of an extinct animal’s life history, scientists are always on the hunt for more clues – specifically, context clues. These clues come in all manner of different shapes and sizes. They could be in the form of fossilised plant life or footprints preserved in the rock. They could be bite marks on other animal fossils or traces of environmental events. Or, as is shown in the Walking With Dinosaurs episode, The Orphan, they can come in the form of enormous poos.

Forms of evidence such as these are crucial to building up that wider understanding of an animal in its environment, and sometimes it is only by examining a variety of clues in context with their environment that we can get that full picture. The Walking With Dinosaurs team took three years to produce the series and during that time they stayed in close contact with the scientists working on the featured dig sites. Whilst actual filming took place over a single dig season, the length of production meant that in this period the experts led multiple excavations at the dig sites without a film crew present. But they always fed their findings back to the production team so they were up to date with the latest and most incredible discoveries.

scientists use material from all over Hell Creek to inform our understanding of the apex predator

Specimens were regularly removed by the experts and taken to the lab for further study – but sometimes, this material is brought back to site, so that palaeontologists can compare it to new material, examine it in context with its environment, or to act as reference points for more fossil hunting. Steve Brusatte, series consultant and palaeontologist, has years of field experience under his belt. “Sometimes when we’re on a dig, we bring fossils we discovered before, so we can compare them to the fossils we’re excavating or to help train our team.” After all, there’s no better way to know what you’re looking for than by having an example right in front of you.

This methodology is used in the episode Band of Brothers where we see Dr Jim Kirkland and Dr Josh Lively examine a strange new bone. Earlier in the episode, we come to learn that this incredible dig site has not only yielded a rare group of Gastonia, but material belonging to an unknown raptor dinosaur. The wider area, known as the Cedar Mountain Formation, is home to multiple different predatory raptors. To identify this mystery killer, the palaeontologists compare the new fossils to existing ones – in this case, a cast of the fearsome killing-claw of the grizzly-bear-sized Utahraptor. A match! But while comparative anatomy like this can demystify the identity of certain predators, learning about other aspects of their lives can require some… unexpected evidence.

In The Orphan, a lump of impressively large dinosaur dung is examined by palaeontologist Eric Lund. By examining this dino-dropping, and discussing possible feeding behaviours with his team, Eric uses the sample to illustrate what delicacy T. rex could have been feasting on: baby dinosaurs. This specimen is to date the largest coprolite discovered, found by George Frandsen, a world-record-holding coprolite collector – it was found further afield in the Hell Creek Formation, the vast outcropping of Cretaceous rock that spans four US states. The tyrant king roamed these lands, and scientists use material from all over Hell Creek to inform our understanding of the apex predator.

Similarly, in the episode, The River Dragon, evidence from across the Kem Kem Beds is crucial to learning more about the risks and rewards for Sobek the Spinosaurus in this rich environment. Thanks to discoveries made by the palaeontologists on the site, we know that this was a water-loving animal. So the scientists wanted to work out what shared these ancient riverways with it – and that means prospecting in rocks all over the Kem Kem. It is by going further afield and by looking in every nook and cranny that Dr Nizar Ibrahim came across the skull of a giant sawskate – a fish with a barbed snout. A perfect meal for Spinosaurus – especially considering the Spinosaurus teeth found in the same river deposits as the prehistoric fish.

To understand dinosaurs and their lives is to peer back through time with a telescope.

The environments any one dinosaur species inhabited were often wide-spanning, both in time and space. In the modern day, many large animals move huge distances over their lives – elephants can traverse tens of kilometres in a day, and an individual Bengal tiger can guard a territory of nearly 100 square kilometres. Extrapolate that onto some of the biggest dinosaurs – these animals would have been leaving clues to their life history (and not just the smelly kind) all over the landscape. “When we’re trying to understand a dinosaur that lived tens of millions of years ago, we behave like detectives, and use whatever clues are at our disposal. Bones, teeth, footprints, fossil poo – if we can find it as a fossil, we will analyse it” – Steve Brusatte

In Island of Giants for example, our palaeontologists venture to the Portuguese coast, some distance from their Lusotitan dig site, to examine giant footprints that are preserved on the cliff face. While we will never know if the same animal buried those miles away left those tracks, we can use them to learn more about the species and what sort of lives these animals would have led – in this case, these trackways showed just how resilient giant long-necked sauropods could be when faced with an injury to their legs.

To understand dinosaurs and their lives is to peer back through time with a telescope. Often, we only get a blurry, distant idea of what their worlds were like – but thanks to the work of palaeontologists, who leave no stone unturned, that idea is shaped and refined with the discovery of every new clue.