The Spinosaurus that was lost in the War

By series assistant producer Sam Wigfield

In 1911, palaeontologists Richard Markgraf and Ernst Stromer, embarked on an expedition in the western desert of Egypt, known as the Bahariya Oasis. After a week of travelling by camel from Cairo, the scientists and their collaborators began excavations in the area. But the fossils they found were not ones you would expect to find in a desert. The remains of fish and even sharks suggested a prehistoric environment containing water, but the fact they were found next to petrified wood meant these creatures lived inland, not in the ocean. The team then uncovered the fossilised bones of creatures which were much less familiar… bones of dinosaurs. A very strange picture of an ancient prehistoric world was beginning to emerge.

The evidence of Spinosaurus’ existence turned to ash in an instant.

Stromer and Markgraf found multiple different dinosaurs, but there was one that was unlike any that had been found before. Clearly carnivorous, with surprisingly long and rounded (rather than sharp and jagged) teeth, the most notable feature was the backbone with huge spines sticking out from each vertebrae. With such a confusing mix of features, it was hard to envisage what this animal could have looked like. Stromer named it Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, the Egyptian Spine Lizard. The bones were added to the Bavarian State Collection of Palaeontology, but with such an incomplete skeleton, many questions about this mysterious dinosaur and the strange world in which it had lived remained unanswered.

And soon even these few bones were to be lost. On April 1944, the allied forces of the RAF and the US Air Force conducted a bombing raid on Munich. Some bombs strayed from their intended targets, resulting in thousands of casualties and the destruction of several buildings, including Munich’s Museum of Palaeontology which housed the Spinosaurus skeleton. The evidence of Spinosaurus’ existence turned to ash in an instant. In the years that followed, the existence of Spinosaurus retreated into almost mythological status. Only the hand sketched drawings remained. Questions circulated, querying whether all the bones even belonged to one type of animal, or if multiple dinosaurs had been Frankensteined together to draw a conclusion.

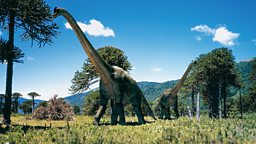

But as science advanced and evolved an understanding of how the remains of sea creatures could be found in the desert began to take shape. Around 100 million years ago, when Spinosaurus roamed the earth, North Africa was a deltaic river system, unrecognisable from the environment of the Sahara today.

All that water moved plenty of sediment. When sediment covers skeletons, it creates the perfect conditions for fossils to form. Minerals in the water slowly flow through, then are deposited in the bones. In time, these minerals take the form of the bones themselves, creating a fossil. Slowly layers of sand build up on top. As time passes and shifting tectonic plates move across the Earth, landscapes can be completely altered and fossils that were once on the coast or even the ocean floor can end up in layers that form the present day's mountains. The fossils remain underneath these layers until they are exposed, typically when natural processes erode the rock surrounding them, but sometimes manmade excavations speed this process up. Palaeontologists looking for fossils often search for fossil fragments scoured from the landscape by erosion before following a breadcrumb trail towards the source. Here, heavy machinery can be used to excavate whatever bones have survived the ordeal of fossilisation, rock stresses and erosion.

The two sets of bones combined could actually be the most complete Spinosaurus specimen in existence...

Normally experts follow the bones, digging one up and then another, leading the way to a whole dinosaur skeleton, but the clues that led palaeontologist Nizar Ibrahim to Spinosaurus made for a far longer search. It began when he first came across a cardboard box of dinosaur fossils in a Moroccan marketplace. The fossils sparked his interest, but there was no information about where they came from and so he thought the trail had run cold.

Later Nizar was invited to the Natural History Museum in Milan to inspect recently donated fossils. But when he looked at them he was shocked – they were same, colour, texture and shape as his Moroccan find. Pulling the bones together and examining them further he realised he had a match. The two sets of bones combined could actually be the most complete Spinosaurus specimen in existence, but to prove that, Nizar would have to find their origin. The only chance to do so was to find the commercial fossil dealer who had sold both sets of bones but Nizar had hardly any information to go on. He returned to Morrocco and searched for many months with his team. They were on the verge of giving up when one day Nizar was having a drink at a café and a man matching the dealers description walked past. The rest, as they say, is history.

The team had to remove 15 tonnes of rock from the site to find more samples. But it was worth it.

Both sets of samples were confirmed to have the same origin. Now not only did Nizar have two sets of matching bones, but he also had a location where the bones had been originally retrieved from. The team had to remove 15 tonnes of rock from the site to find more samples. But it was worth it. Emerging from that site, 70 years after the original discovery was lost forever in a bomb blast, a Spinosaurus fossil more complete than any ever found. This discovery shed new light on how they would have moved, what they would have eaten and how they might have lived, completely redefining our understanding of this incredible creature – and the basis for an incredibly exciting episode of Walking with Dinosaurs.